When Genetics Becomes Personal: Rare Disease, Family, and Genomic Medicine – Reflections from a Centre for Personalised Medicine Research Fellow

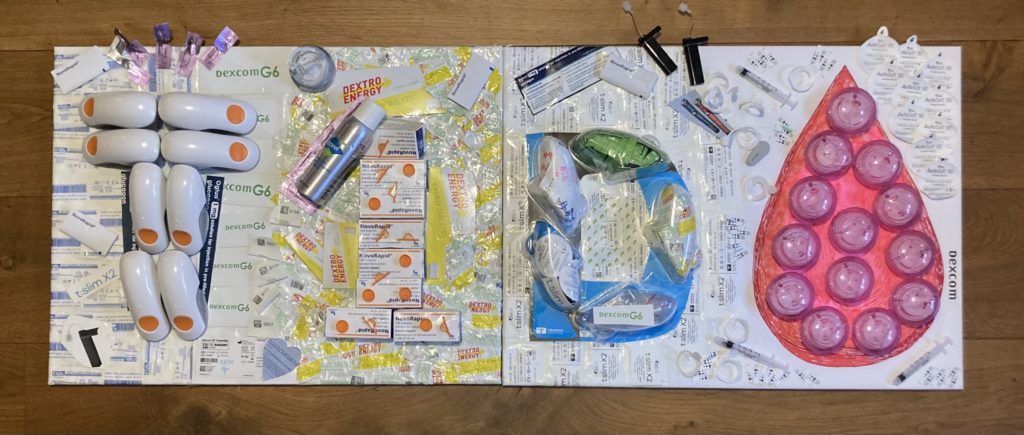

My name is Sally Sansom. I’m a Research Fellow within the Centre for Personalised Medicine at St Anne’s College, and I’m also in the final year of my PhD within the Health Economics Research Centre at the University of Oxford. My work focuses on genomics, rare conditions, and how we decide whether new genomic medicine technologies improve the lives of patients and caregivers, and represent good value for money for health systems like the National Health Service (NHS).

But the reason I work in this area is not only academic, it’s also deeply personal.

A personal beginning

I’m the eldest of three girls. My middle sister, Stephanie, is eighteen months younger than me. When we were growing up, I slowly became aware that she was different. She never said her first word. She barely slept. She had seizures. And, when we were out in public, people stared. I would glare back, wanting to protect my little sister and my family, without really understanding why she was different, or why she wasn’t growing up like I was.

When Stephanie was two years old, she was diagnosed with Angelman syndrome, which is a rare, genetic, neurodevelopmental condition. For the first time, we had a name for what Stephanie, and we, had been living with.

People who haven’t encountered Angelman syndrome often find it difficult to picture what this looks like in everyday life. Stephanie is today what I sometimes describe as an adult-sized eighteen-month-old. She has never spoken. She isn’t toilet trained. She struggles to safely walk independently. And she needs lifelong, around-the-clock care. As a child, all I really understood was that Stephanie needed much more help than other children, and that this help would always come from our parents, and over time, from me and my youngest sister.

Finding meaning through genetics

For me, Angelman syndrome didn’t just explain Stephanie. It also gave me a framework for understanding the world. This became particularly clear to me when I was fifteen years old, sitting in science class.

I remember being handed a piece of paper with forty-six squiggly lines printed on it. Each line was a slightly different length, with a different pattern of dark and light bands. We were asked to cut them out and arrange them into height order. Slowly, it became clear that the squiggly lines weren’t all different, they belonged in pairs. Twenty-three pairs, to be exact.

Our teacher explained that these squiggly lines were chromosomes, and that they were made up of the genetic material (or DNA) that makes us who we are. Every person’s genetic material is different, and that’s why every person is different.

I looked at the pair of chromosomes labelled “15”, and suddenly something clicked. One tiny error, in one tiny section of just one of those chromosomes, answered the question I had been asking for years: why is my sister different?

Genetics gave me a way of understanding how Stephanie came to be, what her future might look like, and how I might be able to help her. It’s why I studied genetics in my undergraduate degree, and later why I moved into health economics: because scientific discoveries, like genomic medicine, can only change lives if they move from the laboratory, through clinical testing and evaluation, and into routine healthcare.

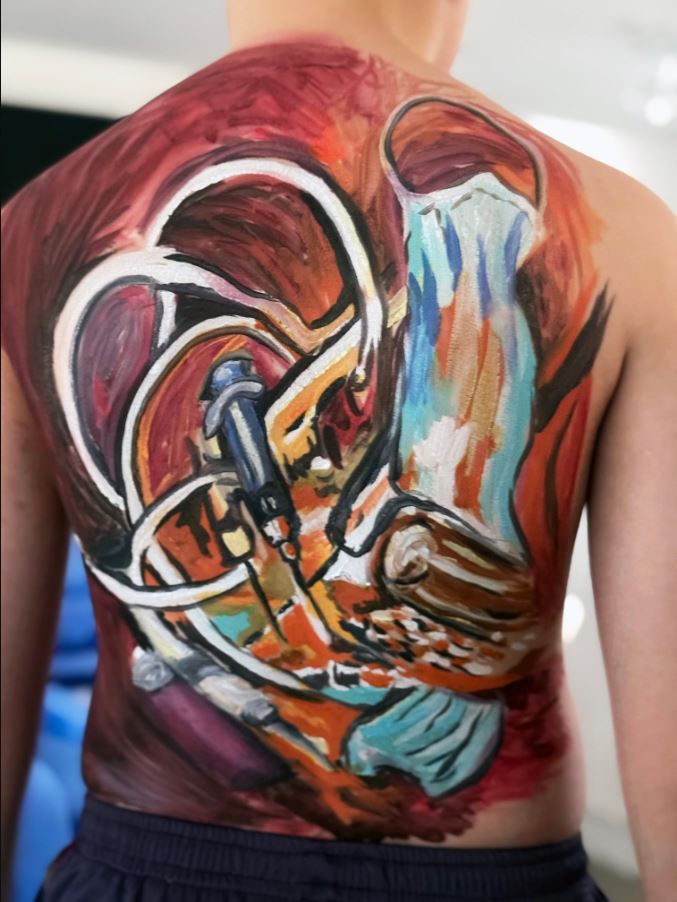

Genomics and gene therapies

I like to think of our DNA as the architectural plans for a house. Every cell in our body contains a complete copy of those plans. They are extraordinarily detailed, and they describe how the house should be built, how it should function, and how it should be maintained over time.

Genome sequencing is the process of carefully reading those plans, letter by letter. It allows us to identify when a single letter has been blurred or damaged, when an instruction is ambiguous or incomplete, or when an entire page is missing. For rare conditions in particular, genome sequencing has transformed the process of obtaining a diagnosis. It can bring clarity after years of uncertainty, and can provide a foundation for research into future treatment options.

However, simply reading the plans and identifying the problem doesn’t fix the house. This is where gene therapies come in.

Gene therapies are often spoken about as if they are one single thing, but in reality, they are a broad family of approaches. What they share is the aim of changing the genetic material within our cells, or how it is used, rather than simply treating symptoms.

Historically, when people first talked about gene therapy, they were usually referring to gene replacement therapies. These involve delivering a working copy of a gene into cells that, for whatever reason, are missing this gene, or their copy of the gene is non-functional. In house terms, this is like inserting a missing page into the plans. This approach works best when a gene is completely absent or non-functional, and when the replacement gene is small enough to be delivered.

These types of therapies have already transformed care for some rare conditions. One example in the United Kingdom (US) is Luxturna, which treats a form of retinitis pigmentosa, a rare inherited condition that causes childhood blindness. By delivering a working copy of the gene directly to retinal cells, Luxturna can restore functional vision in patients with just one injection per eye within their lifetime.

But gene replacement therapies are only one option, and they are not suitable for every condition.

A second type of gene therapy focuses on gene regulation. In these cases, the gene is present in the cells, but it isn’t active enough or it’s too active. So, rather than adding a new gene, these therapies aim to increase or decrease the activity of an existing gene. Returning briefly to the house analogy, this is less like adding a new page and more like reinforcing an existing structure.

A third type of gene therapy involves gene silencing. Sometimes the problem isn’t that the gene is missing, or is over- or under-active. Sometimes the problem is that the gene is producing something harmful to the cells. In these cases, the goal is to stop the gene from being used by these cells completely.

More recently, there has been growing interest in a fourth type of gene therapy, involving gene editing. These approaches use molecular tools to make very precise changes to the genes already within our cells. So, rather than adding, regulating, or down regulating genes, gene editing aims to correct the underlying error.

Angelman syndrome illustrates why having this range of approaches matters. The gene involved in this condition is relatively large, and the most commonly used delivery systems for gene therapy can only carry small amounts of genetic material. This means that gene replacement is more challenging. However, it is still thought to be possible, and the first person with Angelman syndrome was dosed with the first gene replacement therapy for this condition in an early-stage clinical trial late last year.

In addition to gene replacement therapies, researchers are also exploring gene regulation therapies for Angelman syndrome. These are thought to be promising because individuals with Angelman syndrome often have a functional copy of the gene present within their cells that is silenced, so these approaches are looking at methods for turning this gene back on.

An important consideration is how gene therapies are delivered. Some are given directly into the body, for example into the bloodstream or into the fluid around the brain and spinal cord. Others involve taking cells out of the body, modifying them in the lab, and then returning them to patients’ bodies. Some approaches are designed to be given once, with effects that may last many years or even a lifetime, while others may require repeated dosing. Each of these choices has implications for safety, feasibility and acceptability, and cost-effectiveness.

Some gene therapies are already being used in the UK for rare conditions. In addition to Luxturna, another example is Zolgensma, which is used to treat spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA. This therapy replaces a missing gene in very young children and can dramatically alter the course of this condition that was once almost universally fatal in early childhood.

Why evaluation matters

These advances are extraordinary, but they also raise difficult questions. Many gene therapies are extremely expensive. Some are given only once, with effects that are intended to last a lifetime. However, the benefits may take years to fully emerge, and the long-term risks are still being studied, raising important questions about safety, durability, and unintended consequences, particularly when changes are permanent.

This is where my work sits. My research focuses on how we evaluate genomic tests and gene therapies. How do we measure whether they improve lives? How do we capture outcomes that matter, not just changes seen on scans or in lab tests, but changes in communication, independence, and functioning? How do we account for the impact of these therapies on caregivers? And how do we decide whether these therapies represent value for money for the NHS, given resources are limited and needs are many?

For rare conditions, these questions are particularly important. Conditions like Angelman syndrome affect a relatively small proportion of the population, but their impact on the quality of life of patients and caregivers is profound. Parents often have to reduce or give up paid work. And, siblings may take on caregiving roles. These effects extend far beyond individual patients, and can shape family life for decades. Traditional economic evaluation methods do not always capture this full picture very well.

That is why my work focuses on patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes: listening carefully to patients and families, and ensuring that the questions we ask reflect what matters to them, and to their loved ones with a rare condition. It also means being honest about uncertainty. These therapies are promising, but they are not simple fixes. Timing matters. Effects vary between individuals. And, long-term follow-up is essential.

When I think about Stephanie, I often wonder how things might have been different if some of today’s tools had existed when she was born. I feel real hope when I look at the pace of progress. I also feel a strong sense of responsibility to ensure that the widespread excitement about gene therapies is matched by robust evidence, so that patients and families are not offered false promises, and so that a public health system like the NHS can use its limited resources wisely.

So, if there is one thing I hope readers take away, it is this: genomic medicine is creating genuinely exciting possibilities for people with rare conditions and their families. But those possibilities must be accompanied by rigorous research and evaluation, thoughtful decision-making, and a clear focus on outcomes that matter.

References

A. Schambach et al., “A new age of precision gene therapy,” The Lancet, vol. 403, no. 10426, pp. 568-582, 2024, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01952-9.

E. James. Foundation for Angelman Syndrome Therapeutics (FAST). Introduction to Gene Therapy. (2025). Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q4VcMmJCWU8.

Foundation for Angelman Syndrome Therapeutics (FAST). “The State of the Drug Development Pipeline.” Foundation for Angelman Syndrome Therapeutics (FAST). Available: https://cureangelman.org/current-pipeline.

N. Vokinger, C. E. G. Glaus, and A. S. Kesselheim, “Approval and therapeutic value of gene therapies in the US and Europe,” Gene Therapy, vol. 30, no. 10-11, pp. 756-760, 2023, doi: 10.1038/s41434-023-00402-4.

M. F. Drummond et al., “Analytic Considerations in Applying a General Economic Evaluation Reference Case to Gene Therapy,” (in eng), Value Health, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 661-668, Jun 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.03.012.