Centre for Personalised Medicine Art Competition 2023-24

In the second year of the competition, we looked at screening newborn babies for disease. All babies born in the UK are offered tests shortly after birth to check for health issues:

- They have a baby check after birth, then again when they are six weeks old where a clinician checks them over looking for issues like heart murmurs, eye problems or clicky hips

- They have a bloodspot test at around five days old where some drops of blood are collected from their heel. This blood is tested for nine rare conditions where treatment before the baby begins to seem poorly is important to help the baby stay as healthy as they can.

Currently, the Newborn Genomes Programme is exploring how looking at a baby’s genetic code might help with checking them for diseases. This sort of testing can look for a lot of diseases at once, but the results might be less clear as we are still learning how a person’s genetic code links to the illnesses they develop.

- A small number of babies will be found to have a disease that can be treated better the earlier you know about it

- For some babies, screening might raise worries that they will become unwell at some point in the future, but it might take years until we can be sure whether they actually will get ill or not

- For most babies, screening won’t raise any health worries, but their genetic code will become part of the project database.

The video introducing the competition can be found here.

The artworks were judged on:

- Relevance – does the image communicate something important about screening newborn babies for disease?

- Originality – does the image make you think about newborn screening in new or challenging ways?

- Artistry – does the image capture your attention and make you want to find out more?

A huge thank you to the judges; Dr Rachel Horton (CPM Junior Research Fellow), Dr Ali Kay (CPM Junior Research Fellow), Dr Kate Keohane (St Anne’s College/Ruskin School of Art), Brian Mackenwells (Centre for Human Genetics), Melville Nyatondo (Oxford Personalised Medicine Society) and Taisiia Sazonova (Oxford Personalised Medicine Society).

We were so impressed with the quality of the entries we received. This blog post talks through the winners and finalists – we hope you enjoy these thought-provoking entries as much as we did.

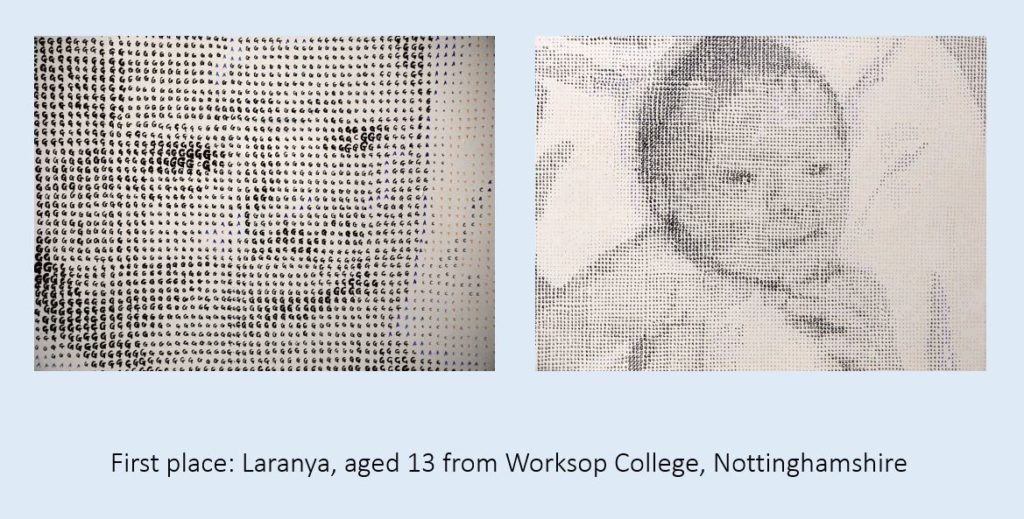

Winner

Our winning entry is this fantastic piece by Laranya, aged 13 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. Laranya produced this artwork using the letters ATGC – the types of bases found in a DNA molecule. Laranya wrote, ‘When viewing the picture up close you only see the letters, but when you look from a distance you can see the face of the baby. This shows that when examining our DNA, you must look with a microscope, and these tiny proteins make up a whole person.’

The judges were captivated by this impressive piece of art, and thought it was great how it showed the challenge of detecting health relevant genetic variation.

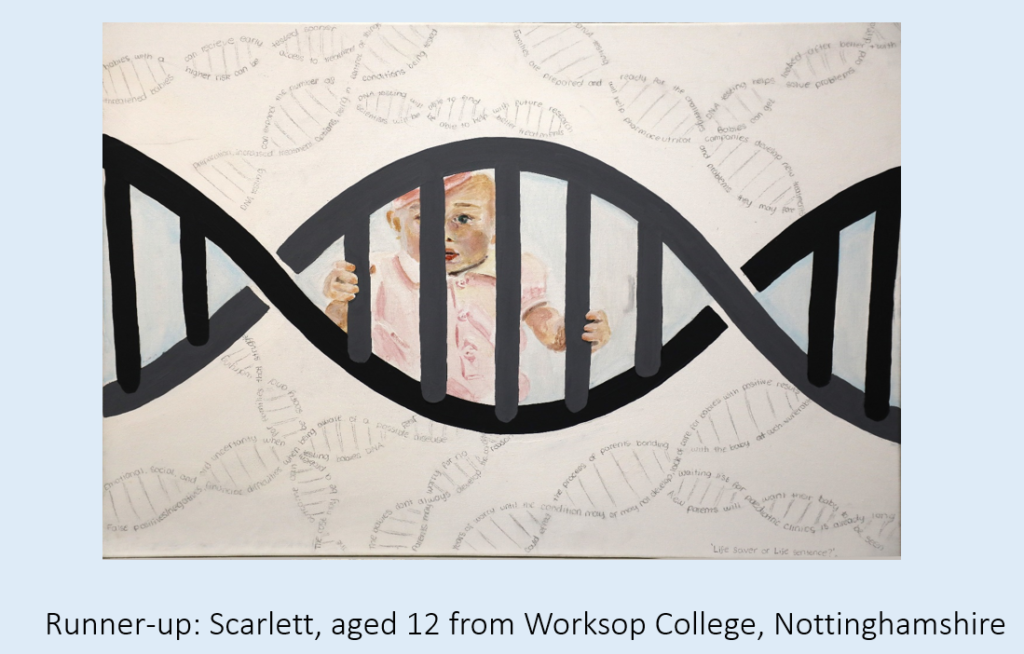

Runner-up

Our runner-up is this thought-provoking entry from Scarlett, aged 12 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. Scarlett wrote. ‘I created a painting that explores the connection between a baby’s future and their genetic makeup. In the centre of the artwork, I depicted a cute baby positioned behind a prominent DNA double helix. The double helix appears like a protective cell, symbolizing the delicate nature of a newborn’s life. Surrounding the baby and the DNA structure are intricate double helix patterns, illustrating the complexity of genetic testing. The intertwining patterns convey the idea that our genes hold a blueprint for our future.’

The judges really liked this artwork, and how it covered the complexities of newborn screening in a captivating and evocative way.

Highly Commended

We were really lucky to receive so many great entries from incredibly talented students – all the following artworks were highly commended by the judges.

Parampreet, aged 11 from Higham Lane School, Warwickshire. The judges thought this was a very vibrant and eye-catching piece covering different elements of health monitoring for newborns.

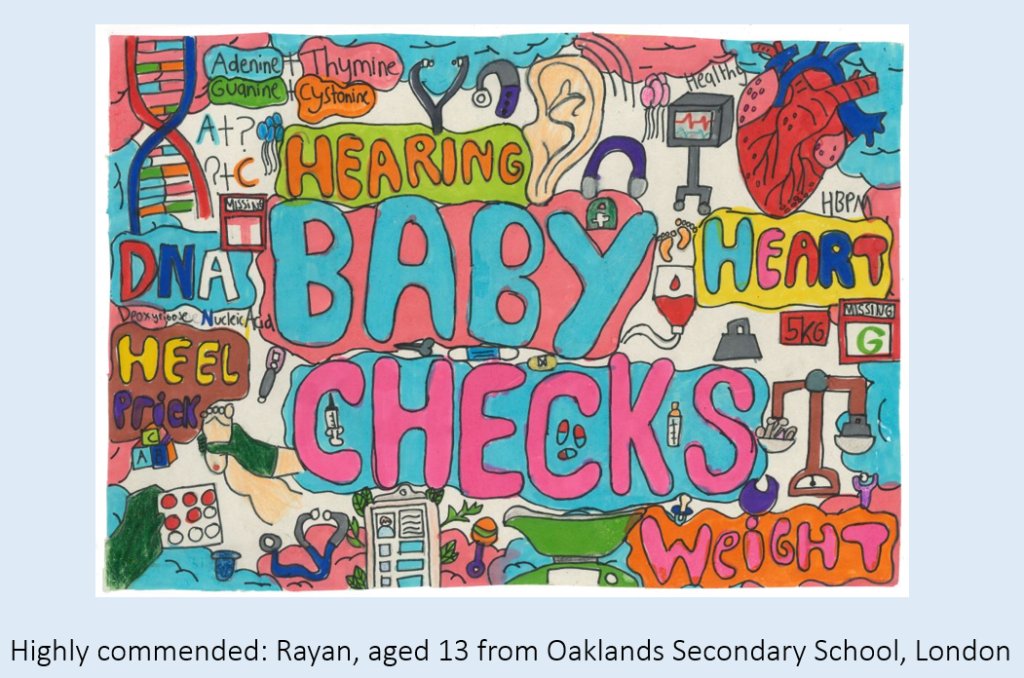

Rayan, aged 13 from Oaklands Secondary School, London. The judges really liked how colourful and informative this entry was.

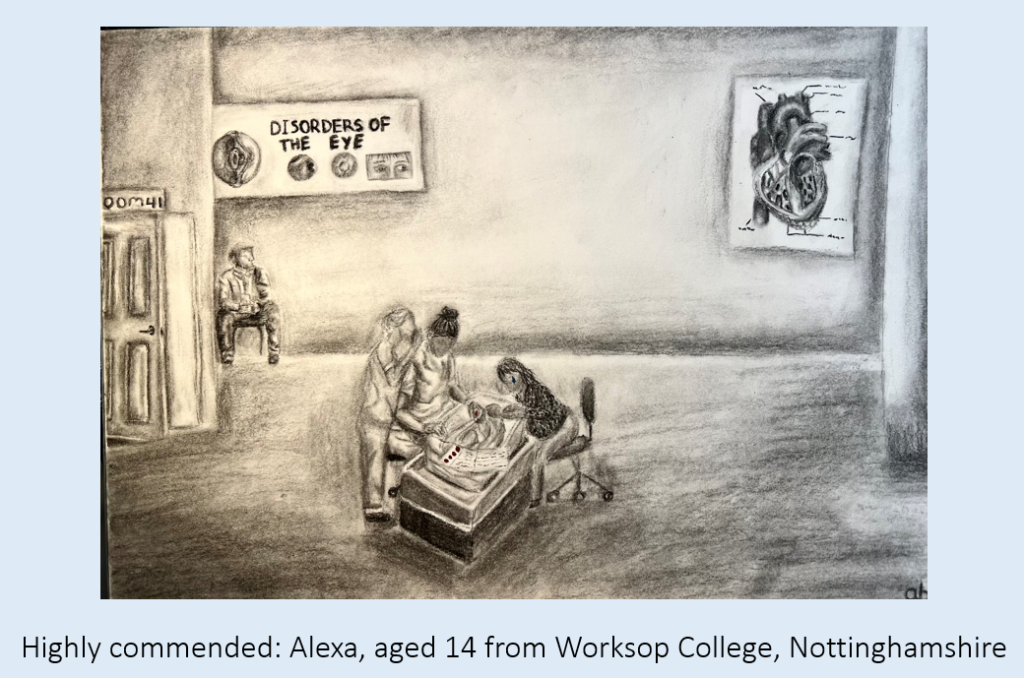

Alexa, aged 14 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. The judges were really impressed by this illustration, and how the use of colour conveys the heavy emotions that come with newborn screening.

Lewis, aged 13 from Biddick Academy, Tyne and Wear. Lewis wrote, ‘My artwork was inspired by the checks performed at birth to newborns. The colours were inspired by the typical colours of blankets and hats in hospital nurseries and neonatal intensive care units.’ The judges really liked the originality of this entry.

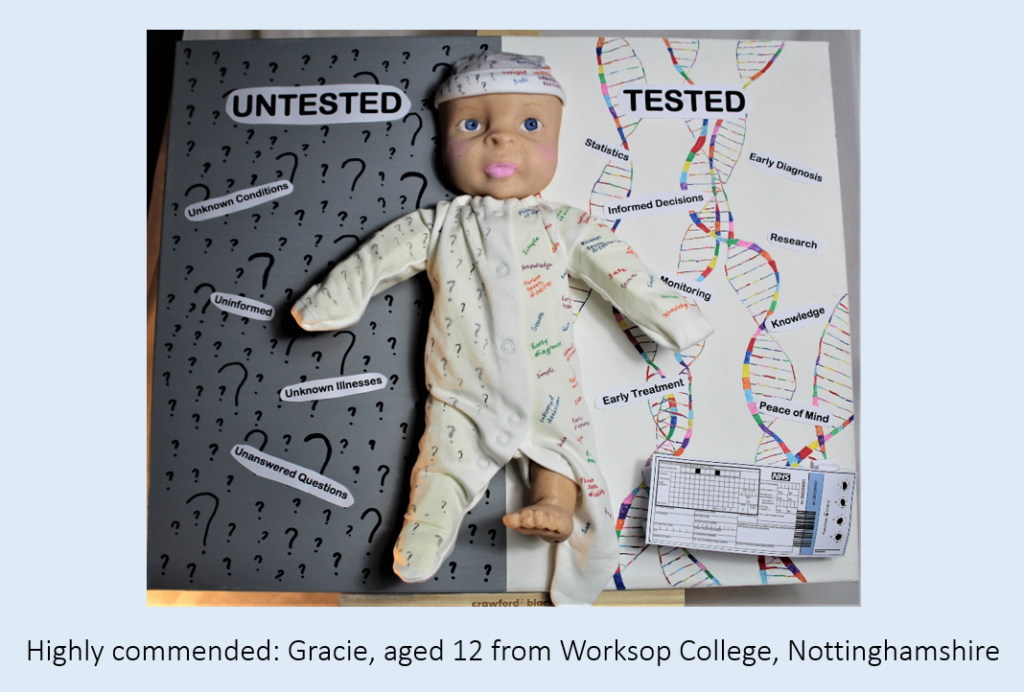

Gracie, aged 12 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. The judges thought this entry was very informative, and it was good to show the pros and cons surrounding the newborn screening topic.

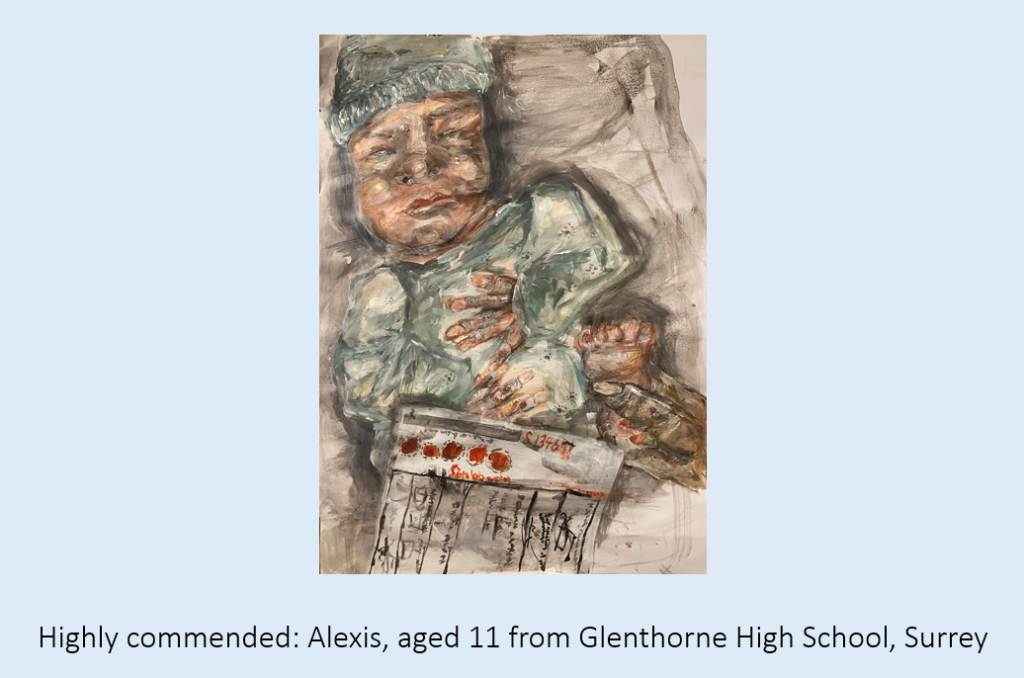

Alexis, aged 11 from Glenthorne High School, Surrey. The judges thought this was a great painting.

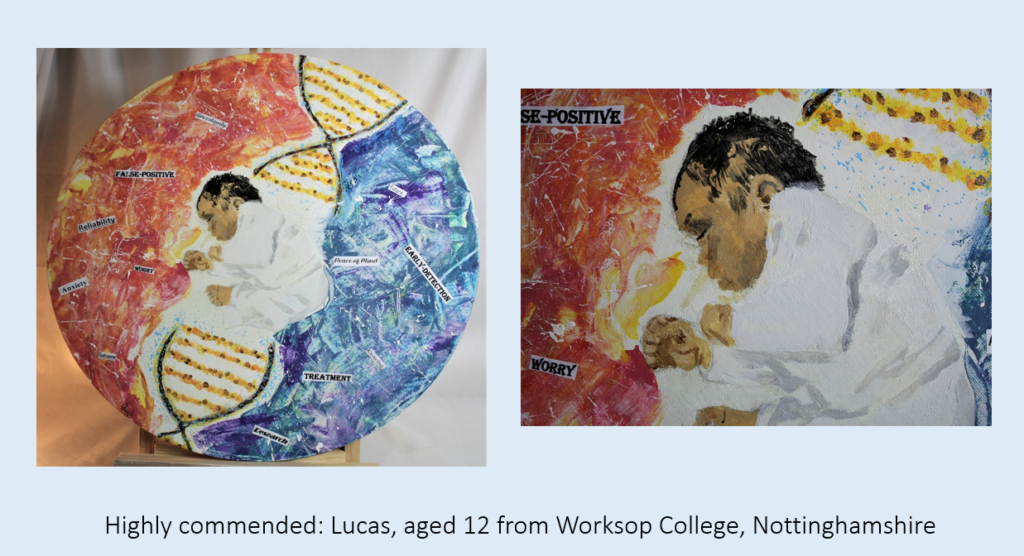

Lucas, aged 12 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. The judges liked how this artwork showcased the double-edged nature of expanding newborn screening. They thought this entry showed a lot of skill, whilst being very informative.

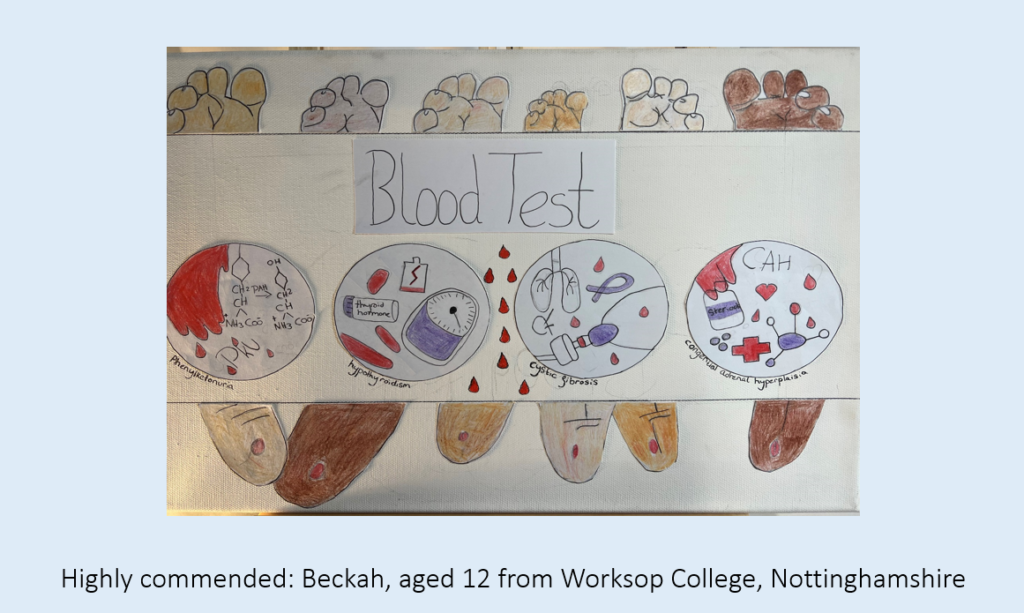

Beckah, aged 12 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. The judges liked how this entry emphasised the public health aspect, with lots of babies undergoing the heelprick test.

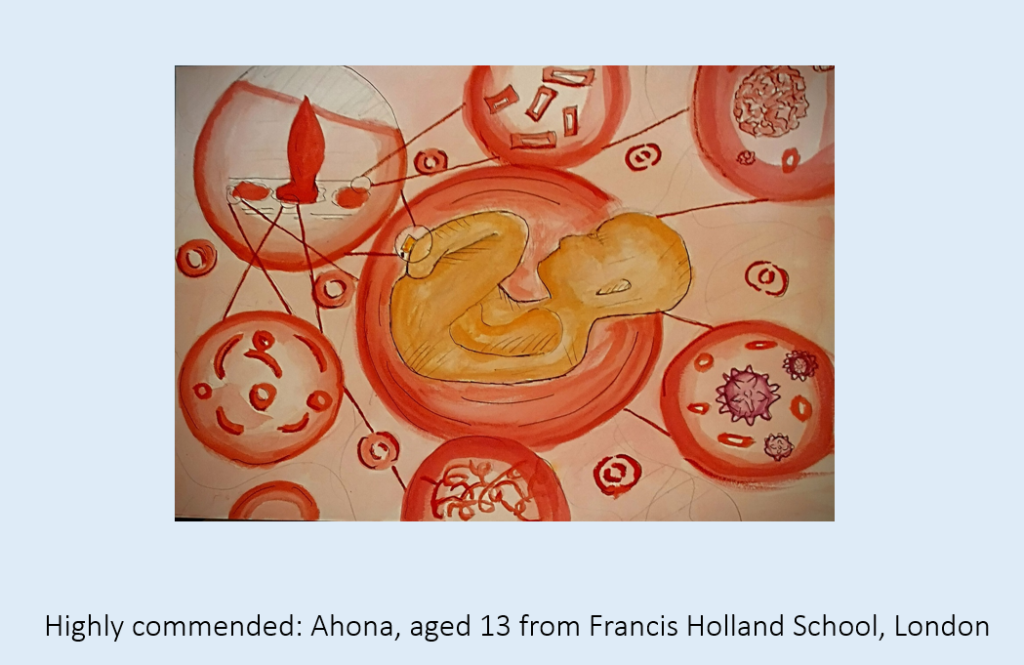

Ahona, aged 13 from Francis Holland School, London. Ahona wrote, ‘I decided to represent the different diseases or viruses that are found in the blood during the blood test of screening babies, and illustrating what the shape of the blood cell or virus would be.’ The judges thought this was a great entry displaying the power of just how much a small bit of blood can uncover.

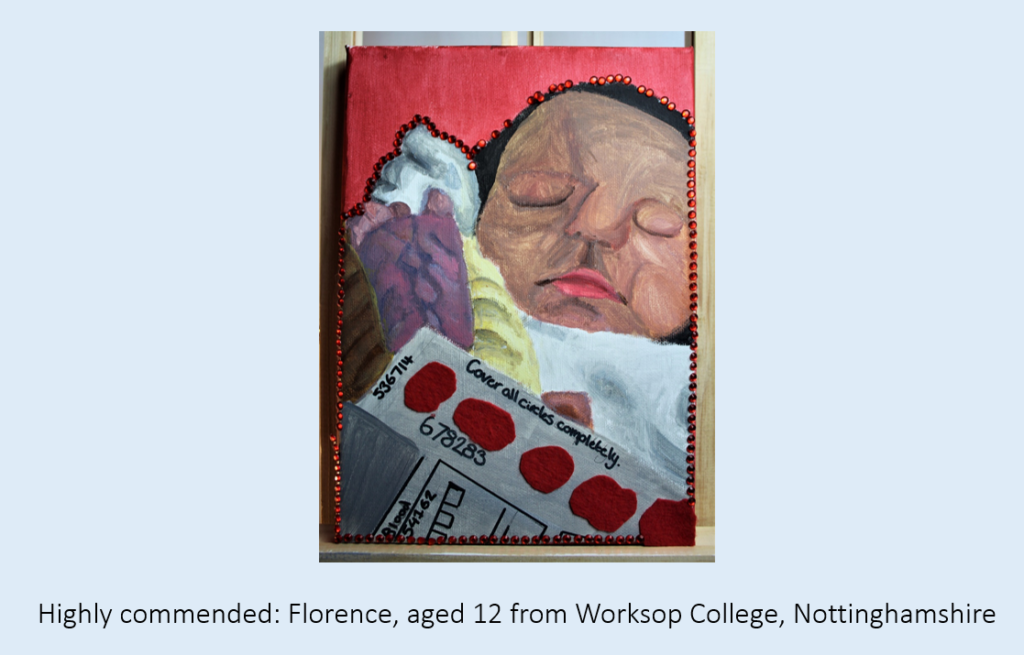

Florence, aged 12 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. The judges thought this was a lovely painting and nice composition.

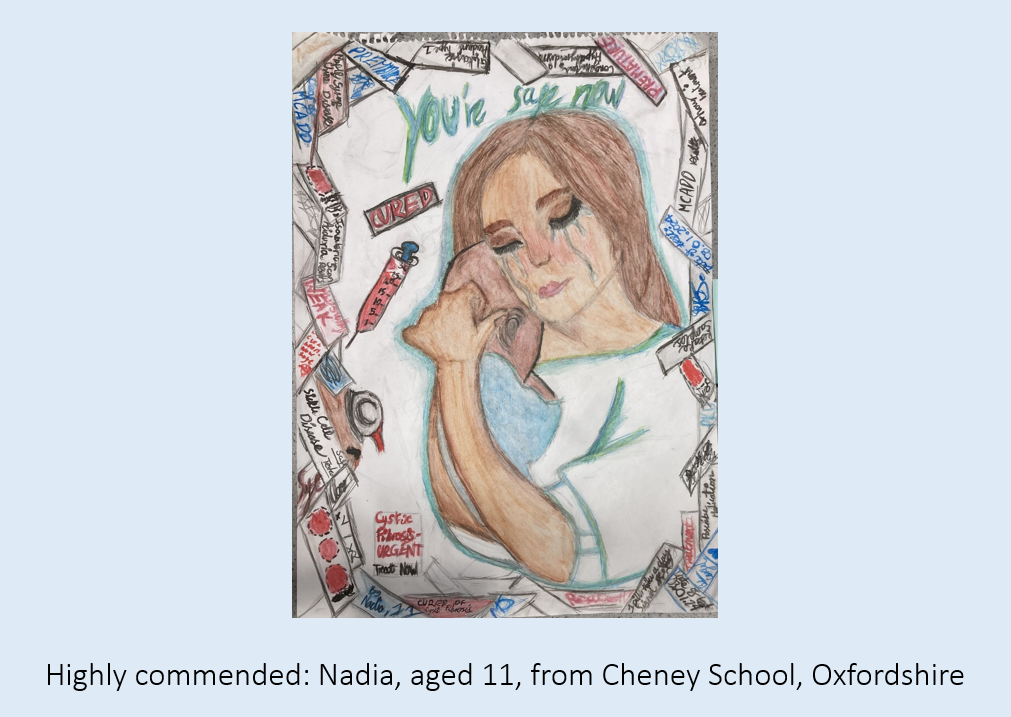

Nadia, aged 11, from Cheney School, Oxfordshire. The judges liked how this drawing showed the potential impact of newborn screening, with significant emotional impact but also the hope that hearing difficult information now will keep the baby safe in the future.

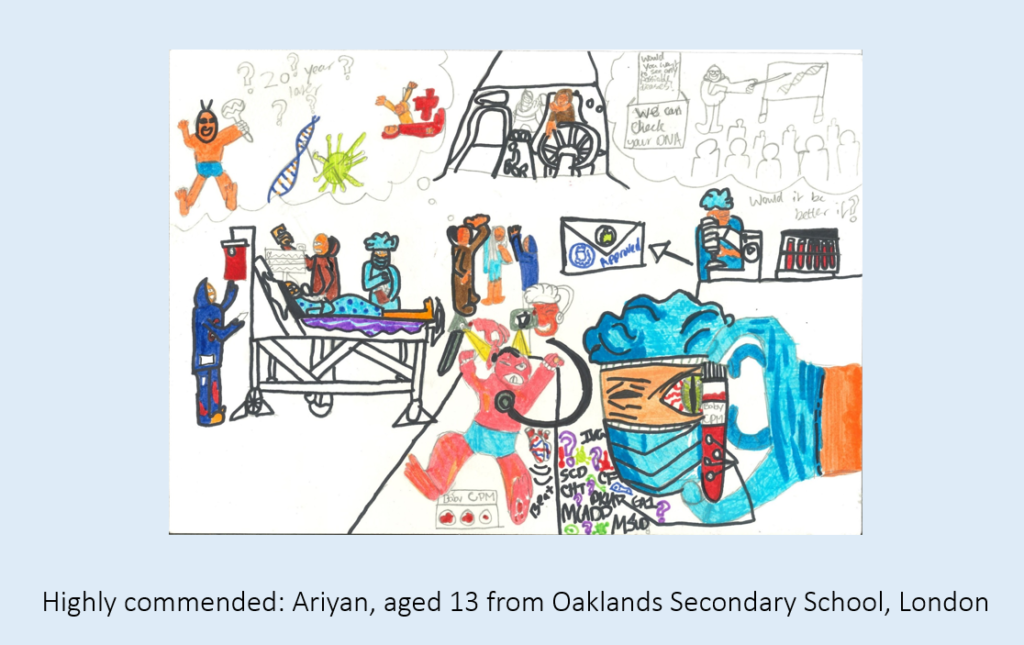

Ariyan, aged 13 from Oaklands Secondary School, London. The judges thought this entry was very informative. Ariyan wrote about how their entry showed the screening of a baby from the heel prick test through to looking at DNA.

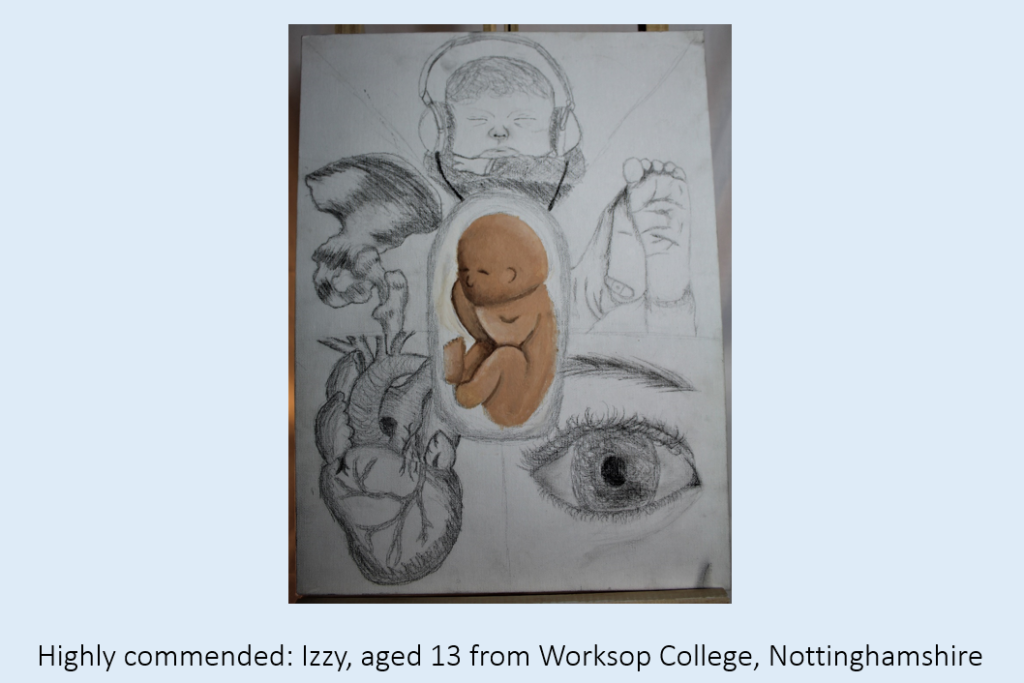

Izzy, aged 13 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. The judges liked how this picture highlighted various different issues that might come to light via newborn screening.

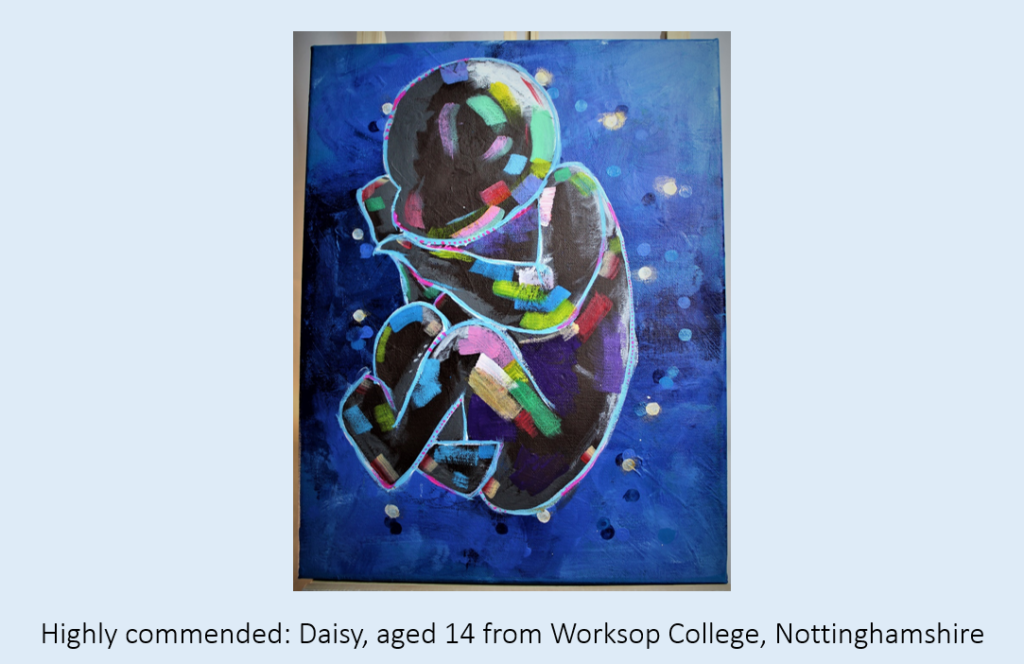

Highly commended: Daisy, aged 14 from Worksop College, Nottinghamshire. The judges really admired the artistry of this painting.

Congratulations to all of our winners and finalists, and thank you to everyone who entered this year’s competition.